Ontario budget weighs tariff threats, ignores climate threat

The Ford government bars congestion pricing in Ontario and reiterates pledges to build highways, nuclear...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

Donny Sutherland’s childhood was defined by the countless hours he spent playing manhunt and other playground games in Constance Lake First Nation. As soon as school let out, Sutherland and his buddies would race into the lush medley of poplar, pine and spruce, rolicking through the brush, sweat and laughter filling the air.

But in 2021, a life-threatening fungal infection swept through his community, claiming five lives and sickening many others, including Sutherland’s brothers. Blastomycosis is a pulmonary illness caused by a fungus that grows in moist areas, particularly soil or decaying vegetation. The exact origins of the blastomyces have yet to be identified, and a paranoia lingers among the members of Constance Lake First Nation like a sliver embedded deep below the skin.

Sutherland shares a common hypothesis with many of his community’s members, that rotting wood left by industry is the host of the fungal outbreak.

For Sutherland, the sickness that plagues his community is a symbol of the devastation that unbridled industry can bring — and an omen for what’s to come if Bill 5, the newest bill from the Ford regime, is passed into law.

Quietly announced amongst the political hullabaloo in the last days before the federal election, the Protect Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act contains a number of proposals that have alarmed environmental scientists and First Nations. Among them is flattening the Endangered Species Act by repealing mandatory protective measures in exchange for discretionary treatment by the province.

One section of the bill that contains massive legislative change is enacting the Special Economic Zones Act. This proposed law will consolidate absolute power to the province for “designated projects” within certain geographic areas. In layman’s terms, as long as a project can be argued as a monetary benefit or necessary for the province, the Ford government can exempt industry from both provincial and municipal laws. The act makes zero mention of the province’s constitutional duty to consult with Indigenous nations — a deafening silence some say could side-step Indigenous Rights completely.

“They only care about one thing and one thing only, and that’s money,” Sutherland said. “They don’t think any further than that.”

In addition to the environmental concerns it raises, Bill 5 is also vague about the circumstances in which the province can act with impunity. Constance O’Connor, a director at Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, is highly concerned by the lack of specificity in what kinds of laws can be bypassed. As it stands, Bill 5 would grant the provincial government the ability to ignore labour as well as health and safety laws, O’Connor explained, putting fair wages and safe working conditions at risk.

“It just seems to be a blank cheque,” O’Connor said.

“There’s no precedent for this kind of exemption in Canada, and the potential for corruption is huge.”

On April 25, Ontario Minister of Energy and Mines Stephen Lecce held a press conference in Thunder Bay, Ont., to talk about Bill 5. Set up in a garage, six men in hard hats, reflective vests and steel-toe boots stoically stood in the back with a Canadian flag hung prominently above their heads. Beyond the men, tucked in among the naked trees, were RPM Drilling’s crimson trucks.

Rebecca Thompson, the vice-president of public affairs at Alamos Gold, the mayor of Thunder Bay, Ken Boshcoff and the MPP for Thunder Bay–Atikokan, Kevin Holland, all stood in front of the workwear-fitted men as Lecce stepped up to a podium fitted with a “Protect Ontario” sign.

While Lecce reiterated the province’s commitment to meaningfully consult First Nations, turning to look upon two chiefs standing off-screen, he continued with the need for Bill 5 under the current economic threats from the U.S.

“It’s about building for the future. It’s about creating a system that works better for us here in Canada,” Lecce said.

Rather than taking the hatchet to existing legislation, some say the Ontario government should instead focus on a better strategy to fulfill its duty to consult.

Unlike British Columbia, Ontario has not passed legislation to enact the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which compels governments to ensure mining claims are secured and developed with respect for natural laws and the prior informed consent of Indigenous communities.

As Jamie Kneen, a co-founder of MiningWatch Canada, explained, the provincial government currently notifies an Indigenous nation about any permits companies have applied for on their territories. Following the alert is a 30-day period for community questions and pushback. In practice, Kneen said the province issues First Nations band offices an endless stream of permit documents, making it logistically impossible to carefully consider each one. If the nation fails to reply to any one of the notices in the pileup of permits within 30 days, “then they just keep going.”

Rick Cheechoo has firsthand experience with this form of government consultation and the struggle to respond in the allotted time. Cheechoo was an elected Moose Cree First Nations councillor for 12 years and has been a member of the nation’s land and resource secretariat since 2002. In addition to the sheer volume, Cheechoo said meaningful engagement is not a quick process that can always be completed in 30 days. Once a permit is received, nations are tasked with their own community consultation process to identify who could be affected by the proposed mining activity, consulting with knowledge keepers to research possible mining impacts and scoping out the land identified in the permit.

A single notice can take four non-consecutive weeks to meaningfully engage with, and Cheechoo said Moose Cree usually receives four new permits every month. The nation is constantly playing catch-up, and as a result, he said it was largely up to the mining companies’ discretion to respectfully work alongside Indigenous communities. In instances where they have not, Cheechoo says the government has not stepped in. While he emphasized that he was speaking as an individual and not a representative of the Moose Cree government, he added that many community members share his concerns.

“We’re not against development. We are for things to be right — to be done properly,” Cheechoo said.

If Bill 5 passes into law, it is unclear what changes to the consultation process will take place. While the current procedure is flawed, said Kerrie Blaise, the founder of Legal Advocates for Nature’s Defence, it’s still valuable as a mechanism that informs Indigenous communities about developments on their land, at the very least, according to Blaise.

“This is not discrete in any way. This is a blatant ‘We don’t care about your voice. You don’t need to participate. We’re going to create a law where industry trumps everything,’ ” Blaise said.

Bill 5 has already passed second reading. While currently being reviewed by a standing committee before advancing to a third reading, the bill will remain open for public comment until May 17. With a majority Conservative government, it has few barriers to becoming legislation, and when it does, it could spell major changes for the Ring of Fire.

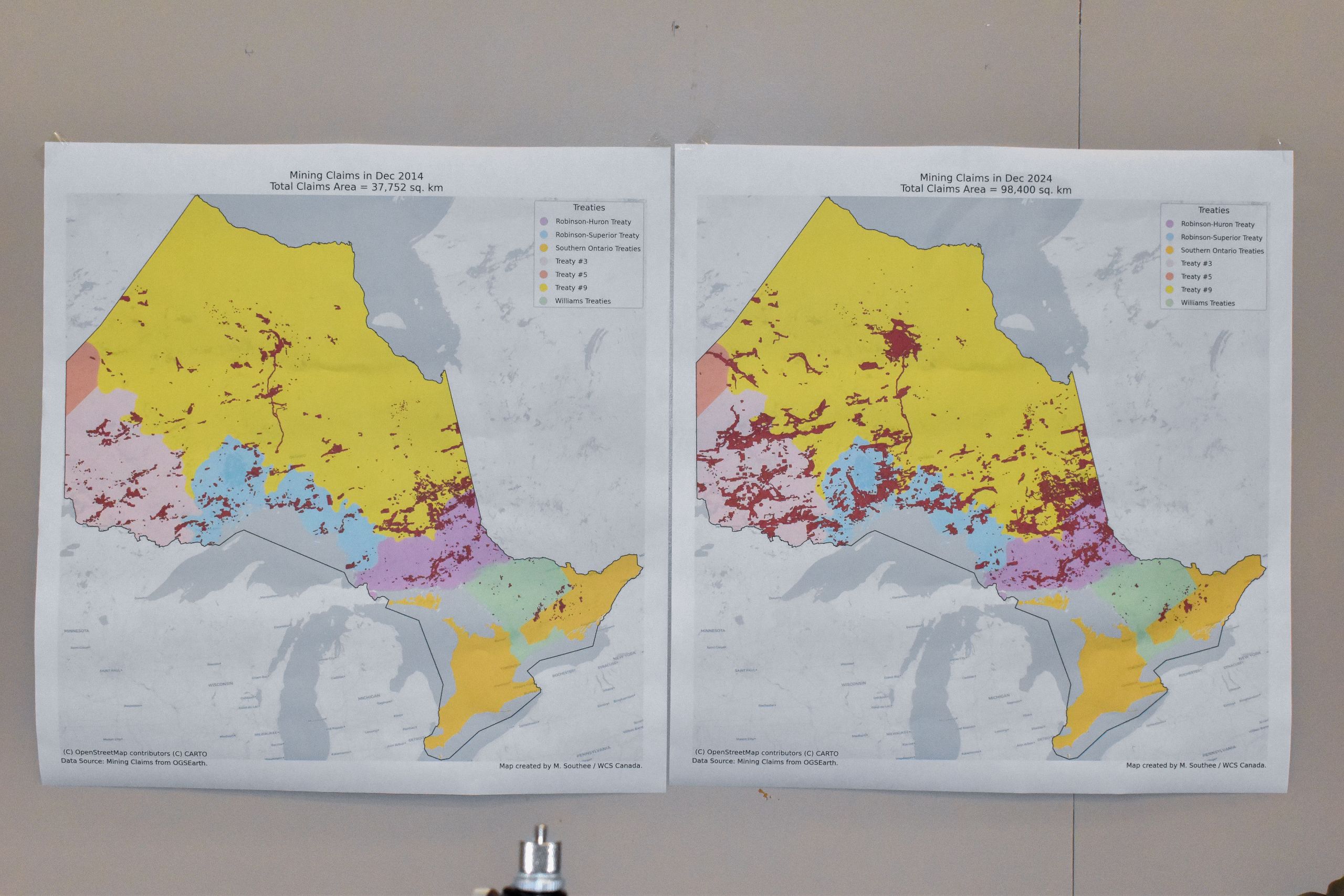

The region, named for the crescent shape of valuable mineral deposits, covers about 5,000 square kilometres in the northern part of Ontario within Treaty 9 territory. It’s been the site of conflict between Ford’s government, which has promised to tap its resources, and several First Nations there who have pushed back.

The bill does not specifically deem the Ring of Fire as a special economic zone, but much of the government’s discussions of the new legislation have centred around the area. Lecce specifically mentioned the Ring of Fire in his press conference in Thunder Bay, and the James Bay Lowlands that sprawl across the mineral-rich region have received significant attention since the inauguration of U.S. President Donald Trump and the Canadian federal election.

The Ring of Fire is located along two main waterways, the Ekwan and the Attawapiskat rivers. Despite the rivers’ ability to transfer pollutants to neighbouring communities like a carcinogenic superhighway, Ford has said it is “ridiculous” to consult with First Nations hundreds of kilometres away from the mining district. But Blaise said these communities will bear the brunt of the ecological damage and will likely have zero notice of its arrival.

“Those changes take time for toxins to build up in the environment. So I would really worry at that point if you’re seeing the contamination, when did it happen? Is it ongoing? Is it reversible?” she said.

The Narwhal reached out to the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade, the Ministry of Energy and Mines, the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, the Ministry of Indigenous Affairs and First Nations Economic Reconciliation, the Ministry of Natural Resources and the attorney general’s office. None of them responded to requests for comment.

Downstream from the Ring of Fire, Attawapiskat cannot afford to endure any more ecological hardship. Attawapiskat has not had clean drinking water for decades, teetering between states of emergency due to high levels of chemicals that have been shown to increase the risk of cancer.

Michel Koostachin has lived with this water crisis for as long as he can remember. He’s seen many people in his community pass away from cancer, including his own father. With chemicals linked to cancer already present in his community’s water supply, Koostachin is terrified of what could happen if the province starts mining the deposit of chromite in the Ring of Fire and smelting it in place.

Chromium-6, also known as hexavalent chromium, is a byproduct of smelting chromite, a key component of stainless steel. This carcinogenic chemical is linked to a motley crew of ailments that can manifest in every major biological system in the human body. Chromium-6 was also the contaminant that leaked from a Pacific Gas & Electric wastewater pond into the drinking water in Hinkley, California, the case behind the film Erin Brockovich. A chromite refinery plant that was promised to bring hundreds of full-time jobs to Sault St. Marie, Ont., was halted indefinitely after facing fierce backlash from the community.

Friends of the Attawapiskat River, an Indigenous grassroots organization founded by Koostachin, declared land protections over the Ring of Fire in February, citing the risks of chromite mining and smelting as part of its motive in a community workshop. The group hoped to drum up enough attention to the damage mining could bring to Treaty 9 communities to encourage the province to rethink its plans for the region. Now with Bill 5 on the table, the ecological fate of the James Bay Lowlands hangs even higher in the balance.

“Anything that’s contaminated you can’t touch, you can’t eat, right? So Ontario is using the economic spin to justify, but it’s an attack on our nature,” Koostachin said.

“It’s an attack on our Indigenous Rights.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The Ford government bars congestion pricing in Ontario and reiterates pledges to build highways, nuclear...

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...